Origins:

Over the early 1950s and 60s, the United States was a catalyst for various revolutions and human rights movements. The Civil Rights Movement, Anti-War Movement, Gay Rights Movement, Migrant Worker Rights Movement, Native American Rights Movement and the rise of second-wave feminism all led various student groups throughout the country to become empowered about their futures. This, in turn, allowed students to organize and start the first popular wave of student activism in the U.S.

50 years earlier, a reverend from Ohio named B.H. Shadduck published and distributed a journal promoting the theory of anti-evolution, titled “Jocko-Homo Heavenbound.” This journal and Shadduck’s theories would remain popular until the reverend’s death in 1950, when the idea of anti-evolution would all but fizzle out. Yet somehow, 20 years later, the journal would fall into the hands of Mark Mothersbaugh, who was then a student at Kent State in Ohio.

In 1970, Mark Mothersbaugh and his brother, Bob Mothersbaugh were both students at Kent State University when Mark met Gerald “Jerry” Casale and his brother Bob Casale. Mark introduced his new school connections to Shadduck’s work, who all became obsessed with the absurd, yet relatable theories. Mark had already been interested in pursuing music as a career. Still, the connection over Shadduck’s journal created the inspiration they needed to start experimenting with the idea of forming a band.

On May 4, 1970, Kent State University had become a hotbed for student protest, and the Governor of Ohio, James A. Rhodes, ordered the National Guard to descend on the campus, kettling students and making arrests.

“These people just move from one campus to the other and terrorize the community. They’re worse than the brownshirts and the communist element, and also the night riders and the vigilantes. They’re the worst type of people that we harbor in America. Now I want to say this. They are not going to take over [the] campus” (James A. Rhodes, May 3, 1970).

Despite the unarguably peaceful aspect of this student movement, the National Guard opened fire on the students, killing four, wounding 29 and paralyzing one.

A retroactive FBI investigation concluded that none of the students had fired upon the National Guard.

Jerry Casale was a part of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and had gone out that day to the Commons, a large field surrounded by grassy hills, to attend the protest.

“I remember thinking, “Hmm, I wonder what they’re doing.” They all have gas masks on and you can’t hear anything clearly, but I saw somebody in charge yelling at these two lines of National Guardsmen, and then he made a hand gesture. That is when they started shooting” (Jerry Casale, Rolling Stone interview, May 4, 2020).

Casale witnessed the murder of two of his school friends, Jeff Miller and Alison Krause, during the Kent State Massacre. 50 years later in a Rolling Stones interview, Casale would admit that this traumatising event radically changed his life’s trajectory.

“I believed in the brand that was America a little too much. Once you go down the other path, you realize this has been a history of genocide, racism, inequality, corruption, hacking away at the very tenets of democratic rule of law, power grabs, imperialism, dirty tricks, supporting dictators, CIA … you just go down the whole thing and you realize what a fucking Disneyland-load-of-shit you were sold. I’ve said it often and I mean it, but I don’t think there would have been a Devo if not for Kent State” (Jerry Casale, Rolling Stone interview, May 4, 2020).

Casale credits his experience at Kent State and his introduction to Shadduck’s journal as the source of his idea of devolution. Devolution was a half-satirical, half-serious theory that the band had invented that explained the regressive behavior of society. This idea became pivotal to Devo’s brand and sound, with the band centering around the idea we had already started to ‘devolve.’

“Devolution happened. We don’t need to talk about it anymore. It was an artsy joke and turned out to be true” (Jerry Casale, The Vermont Review).

New Wave:

Devo’s presence in the music industry kickstarted the New Wave movement. New Wave was originally used as a genre classification for any music that came out of the punk rock scene. However, it eventually became its own genre, recognized by its punk influence that evolved to include synths and pop melodies.

New Wave originated in Britain and challenged the rock and disco culture that was popular at the time. While other musicians were trying to create a brand centered around ‘coolness,’ new wave embraced a nerdy, societal outcast feeling. This culminated in a brand-new genre that retained the punk culture, while creating a new sound entirely.

Discography:

With a total of nine studio albums and a vast array of music videos and short films, Devo has left its mark on the world not just as a band but as an art form.

Devo’s debut album, released in 1978, titled “Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!”, entered the music scene, becoming one of their most popular albums. The album charted at No. 78 on the U.S. Billboard chart and No. 12 on the UK albums chart. Devo had previously recorded demos and brought them to an Iggy Pop concert, eventually getting them backstage and into the music icon’s hands. Impressed with the revolutionary sound that Devo had found, Pop gave the tapes to his friend David Bowie, who met with the band and promised to record and produce their first album.

However, since Bowie had become engaged with other projects at the time, he passed off the responsibility of Devo’s first album to Brian Eno. At this point, Devo was still unsigned, so Eno fronted the band the money necessary to record and release the album. Later on, the band would credit their success to Eno’s generosity.

Eno and the band flew to Cologne, Germany, where they worked on the record in a repurposed barn. Despite Eno’s best efforts, the band had a hard time working with the producer, as they felt that Eno wanted the band to sound more polished instead of the raw, messy feel that they were looking for.

Devo’s most popular album was their third, titled “Freedom of Choice.” The album was released in May 1980 and peaked at No. 22 on the U.S. Billboard Pop Albums Chart. Devo’s previous and second album, “Duty Now for the Future” had been unsuccessful commercially so their record company told them that this album had to be a success or they would buy out the remainder of their contract.

With this information in mind, Devo set out to write and record all new songs for this album, whereas for the previous albums, they had recorded songs that they had already written. Additionally, Devo prioritized finding a producer who would work with them and cultivate the sound that they wanted. Their search brought them to Robert Margouleff, who had just finished recording with Stevie Wonder. Margouleff allowed the band to record the songs live in the studio, and then overdubbed the synth and vocals in post, which gave the album its rhythmic feel.

“If you play the record, you’ll hear that the bass, the kick and the rest of the drums are very, very prominent and dry in the mixes, so you feel like you’re standing next to the kit.” (Robert Margouleff, Sound on Sound, July 2008)

Margouleff also shared the band’s obsession with synthesizers, and Devo was able to experiment with different sounds like the Minimoog, Moog Liberation, ElectroComp 500 and a custom-made Moog called a “Devobox.”

“Well, Mark put together a kit from PAiA, and after that we moved right up to our ARP Odyssey and a Minimoog. We got stuck with that setup for a long time. Most of Devo was created on those two things” (Gerald Casale, Tape OP, November 2010)

On this album exists the band’s most commercially popular song, “Whip It.” The song’s lyrics were written by Jerry Casale who got his inspiration from writer Thomas Pynchon.

“I had these “Whip It” lyrics from my attempt at doing a Thomas Pynchon parody. He did a bunch of parodies in “Gravity’s Rainbow,” and I liked them so much that I wanted to do one. So for me, “Whip It” was a parody of the whole Horatio Alger ‘You’re number one, there’s nobody else like you, you can do it’ thing” (Jerry Casale, Flavor Wire, 2009).

Despite Casale’s intended meaning behind the song, the majority of the audience for “Whip It” interpreted the song to be about sadomasochism–a sexual behavior that involves gaining pleasure for inflicting or receiving pain. While the band tried to fight these accusations at first, they eventually gave in and made the music video to feed into these interpretations.

Additionally, the music video was poised to make fun of Ronald Reagan and his previous career in Hollywood westerns, as well as his presidential campaign.

“We knew people would think that. That’s why I made the video I made for the song. I said, “OK, let’s just give ’em what they want, or what they think they want to see — except we’ll be making fun of Ronald Reagan and Americana. At that time, he was campaigning for the presidency on this whole rancher thing with the cowboy hat, on horseback” (Jerry Casale, Flavorwire, 2009).

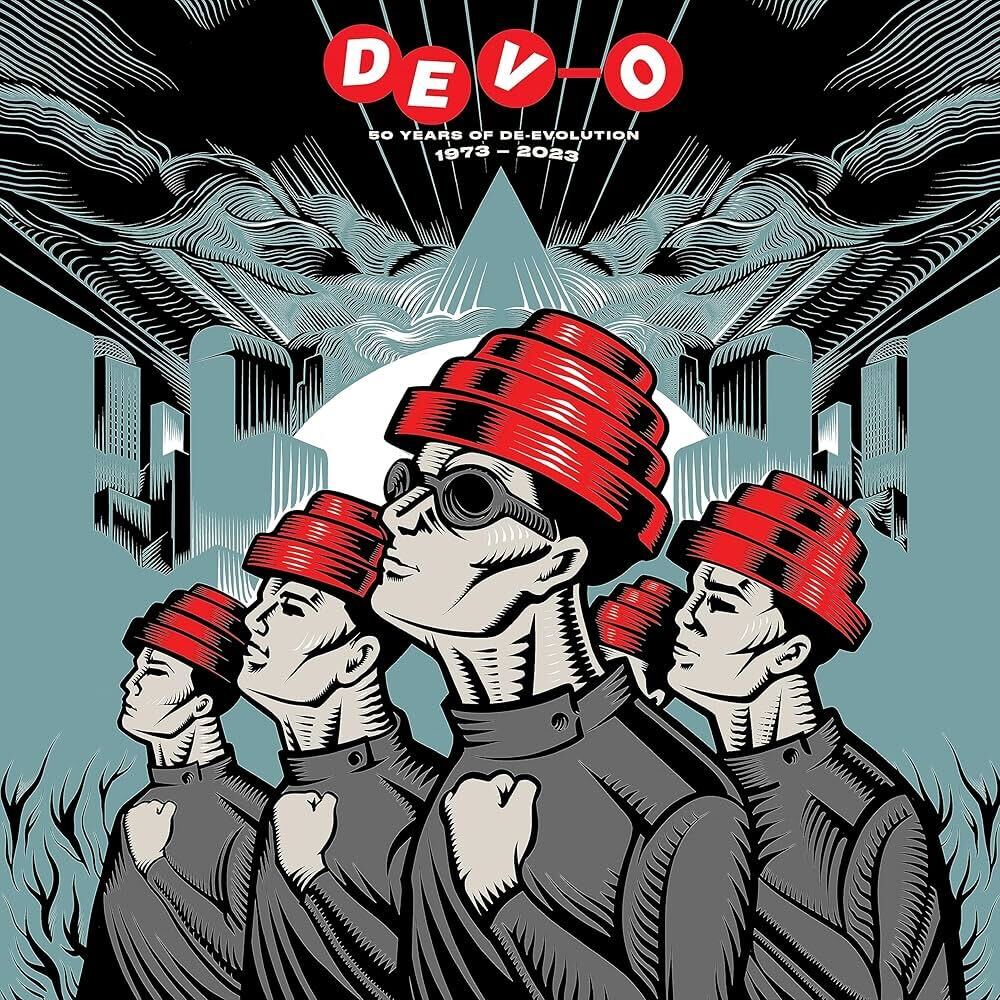

The cover art for the album was also the premiere of what would become one of the most iconic symbols in the history of the music industry: Devo’s Energy Dome.

“It was designed according to ancient ziggurat mound proportions used in votive worship. Like the mounds, it collects energy and recirculates it. In this case, the Dome collects the Orgone energy that escapes from the crown of the human head and pushes it back into the Medulla Oblongata for increased mental energy. It’s very important that you use the foam insert…or better yet, get a plastic hardhat liner, adjust it to your head size and affix it with duct tape or Super Glue to the inside of the Dome. This allows the Dome to “float” just above the cranium and thus do its job. Unfortunately, sans foam insert or hardhat liner, the recirculation of energy WILL NOT occur” (Gerald Casale).

Devo’s bright red Energy Dome became a universal necessity for the most devoted of Devo fans. When attending a Devo concert, one will view a sea of red Energy Domes as a way to distinguish those who are ‘in the know’ and those who are not.

Apart from Devo’s musical career, the band also had an extensive video repertoire, including a short film, “The Truth about De-Evolution” that was filmed in 1976 and directed by Chuck Statler. What is most influential about the production of this video is that it occurred before the popularization of MTV, and very few had bridged the gap between audio and video.

In the film, and some subsequent music videos, we see the debut of some of Devo’s most famous characters, including “Booji Boy”, a masked character made to represent the infantilization and regression of society.

Other impressive visual work from Devo includes their home videos, “The Men Who Make The Music” (1979) and “We’re All Devo” (1983).

After releasing a few more commercially mediocre albums, Devo released their final album, “Smooth Noodle Maps” in 1990. The release of this album marked the end of the band for the time being, as the album’s tour was also a commercial disaster and fell apart halfway through, as the record label had to file for bankruptcy.

What is Devo doing now?

The dissolution of Devo was far from the end of the careers of individual members. Soon after, Mark Mothersbaugh created his own music production house, “Mutato Musika” with the help of his fellow bandmates Bob Mothersbaugh and Bob Casale.

“Mutato Musika” proved to be an extremely successful venture for the Mothersbaughs and Casale. They have been responsible for the soundtracks of popular children’s TV shows such as “Pee-Wee’s Playhouse” and “Rugrats.” They have also worked with legendary director Wes Anderson on some of his most popular films, “The Royal Tenenbaums” and “The Life Aquatic with Steve Sizzou.”

Most recently, they have worked on the music for “A Minecraft Movie.”

While Mark Mothersbaugh had mainly focused on his work for “Mutato Muzika,” Jerry Casale had started to continue his pursuit in video production. The majority of his work focused on music videos for famous bands of the time, such as Rush and Soundgarden.

In 1996, Devo shocked the world and played together for the first time since their split in 1991. Their first performance in five years was right here in Utah, at the Sundance Film Festival. After that, the band played a few shows here and there and released new music. However, since 2023, the band has been on their “50 Years of De-Evolution” tour. Ticket listings on the official Devo website indicate that the tour will end in November 2025.

Devo Fans can look forward to the release of the documentary about the band titled “DEVO” that was filmed in 2024 and shown at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival. Netflix has acquired the rights to stream the documentary and should be available to subscribers on August 19.